Elements 4: Beryllium

Elements 4: Beryllium is the eleventh album in a series of music on the Elements, a very large work in progress consisting of electronically/digitally created architectural music compositions by Oscar van Dillen.

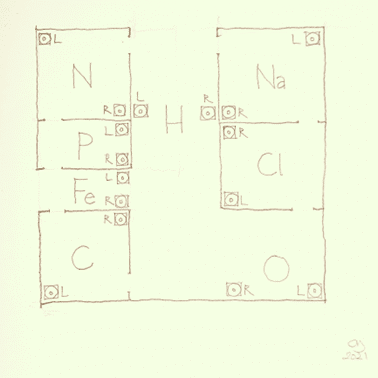

The cover art in the Elements series consists of inverted single line pencil drawings made by the composer.

The work on this album was composed, recorded, and produced December 2022 – January 2023. All works, cover art and booklet of this album were created by Oscar van Dillen.

Other albums in the Elements series so far, in order of release:

- Elements 1: Hydrogen Deuterium Tritium H D T

- Elements 118: Oganesson Og

- Elements 6: Carbon C

- Elements 8: Oxygen – Ozone O

- Elements 14: Silicon Si

- Elements 7: Azote N

- Elements 2: Helium He

- Elements 15: Phosphorus P

- Elements 20: Calcium Ca

- Elements 12: Magnesium Mg

- Elements 38: Strontium Sr

Tracks

- Beryllium – section 1 07:46

- Beryllium – section 2 09:17

- Beryllium – section 3 09:37

- Beryllium – section 4 06:35

- Beryllium – section 5 13:44

- Beryllium – section 6 08:43

- Beryllium – section 7 07:58

- Beryllium – section 8 08:00

- Beryllium complete (one track) 1:11:44

Total duration: 2:23:28

The CD Booklet can be found HERE

On listening to electronic music today

The meaning of the term electronic music has changed dramatically since modern composers started to work with electronic equipment in radio studios after the second world war. In the 50’s and 60’s of the 20th century it meant mostly avant-garde esthetics by an elite group of mostly male composers making the headlines for this at the time niche medium. Today the term changed meaning but at the same time its history is in the process of being rewritten as more and more female composers are being credited for having played a defining role in the development of the medium. In 2021 the acclaimed documentary film called Sisters with Transistors was released, it demonstrated this process for a larger than specialist audience. One can also conclude that on the whole and over time the term electronic music defines a medium rather than a style.

Compositional ideologies played a major role in the times of avant-garde aesthetics, and they still do for many contemporary composers today. In more popular genres this aesthetics has been transformed to a more practical approach to the instruments actually used, with more musicianship involved in the creation of works, and less cold quasi scientific laboratory-like calculations to justify the results (a major consequence and certainly a hobby of the avant-garde ideologues). Today the first thing a young listener will think of when expecting to hear electronic music will be known as EDM, or Electronic Dance Music. Music to party, to dance, to have fun. A starker contrast to the early composed electronic music, say to the times of a Stockhausen and his Etudes I and II and Kontakte can hardly be imagined. Meanwhile the innovative pioneering work of Eliane Radigue was almost completely ignored. What the early electronic composers shared was a very elaborate working process: to create a single minute of music took days/weeks to produce. With the rapid and drastic advances of technology in our times with regards to sound generation and recording this changed completely. What used to take a large studio with very expensive hardware to produce can today be done on a good laptop with professional software, much of it affordable or even free and open source.

When listening to electronic music, one misses the musical instruments such as strings and winds, yet on careful listening there may be sounds referring to these, but more flexible and moving in sound than the physical instrument could ever practically realize. Moreover, with electronic music one misses a musician for every single sound, there may be just one person performing on a laptop, or just a recording, and one stares at loudspeakers (never stare at loudspeakers btw, rather try to locate the sounds instead, as they are not in the speaker but resonating in the room). Most electronic music is however still made by humans and by composers’ choices, the path from human action and sound creation is just somewhat different than playing an instrument, a mouse or a button or a wheel is moved, a bit more technically indirect perhaps, but at the same time producing an audible sound not significantly less instantaneous than playing a live piano would. Moving the mouse, the wheel or the button are of course less visible on stage than a performance on a piano or wind instrument, where an informed viewer can read the keys.

The truly informed listeners to electronic music will be able to recognize historical instruments when used, such as the ARP 2500 or 2600, or the Buchla 200, or the Moog Modular, in case these are used. Each of these iconic and historical instruments can be found again today, mostly in the form of software versions, but now and then in hardware form, all newly made, sometimes with new, sometimes even with “vintage” components. Most modern synthesizer clones reliably reproduce the iconic sound and usage, and sound but slightly different. Hearing the differences between old hardware and modern hard- or software can be similarly a specialist skill as in being able to hear the differences between a Steinway, a Bösendorfer, a Yamaha, a Fazioli, or a Schimmel grand piano – on a recording. Not obvious, not obvious at all, as music is about music first of all and not about musical instruments at all. Still, diehard electronic composers may swear by certain hardware: Moog, Buchla or ARP synths. Likewise acoustic instrumentalists swear by instrument brands and types, Muramatsu or Haynes flutes, Selmer vs Yanagisawa saxophones, Stradivari vs Guarneri or Amati violins, etc.

Specific instruments matter more to performers and should not be made into criteria for listeners. Nevertheless, being able to hear types of instruments is just as important in acoustic as in electronic music. Can one recognize the sound of a clarinet and distinguish it from the oboe, from the soprano saxophone, or the flute? Can one pick up the melody of the bassoon, the French horn, the trombone? Similarly with electronic music: can one hear the wave form types, the sine, the modulated sine, the square and mixed triangle waves in slightly detuned unisons, the types of noise, white, pink, brown? Can one hear certain brands of hardware being used, type of filters or a ring modulator, or the synthesizer itself in case of an iconic known sound?

Most difficult of all: can one hear how a music was made, composed, and produced? Most important of all: can one actually enjoy this music, both with and without all this knowledge and ability to recognize specifics?

And lastly: can we actually let go of the illusion of being in control of that pet we call our mind and let the music and musical perception simply take over and surprise us?

The challenge with innovative contemporary music made for listening per se such as this album, lies in a challenge to connect in a free way, and go through the steps of open perception and appreciation individually, without recipe, without a priori dos and don’ts, without expectations but with memories, with a sense of exploration as in starting a new novel or unknown movie without spoilers:

- Observe – hear everything, don’t be distracted, be aware of what happens in the various registers of time, tone, timbre, space, and volume (the range of each is much larger than with instrumental music): try to imprint what you hear into memory, ask yourself what is it objectively that I heard?

- Evaluate – can you perceive every form distinctly enough, some things may be harder to hear, or are sounds that affect you emotionally or even physically: observe and evaluate the effect of it.

- Interpret – observe your mind creating associations of its own: they are yours and not in the music itself yet are created by the music in you personally.

Ways of Listening to the Elements

The series Elements by Oscar van Dillen consists of medium to long duration digitally created electronic compositions which have a more static, installation-like character, exploring the borderlands between musical and spatial composition, linking up music and architecture, both arts concerning Space. It is a remarkable feature of human anatomy that the ear is the organ that perceives sound as well as space, by hearing and orientation. Inside in the cochlea (inner ear) resonating longitudinal crystals distinguish the frequencies within sound.

Outside on top of the same organ there are the three half-circles of the Labyrinth, perceiving spatial movement along an XYZ axis system. The direct perception of 4-dimensional space-time itself can be seen in this essential part of our anatomy: one organ handling perceptual elements of both space and time in unison.

Space, in the perception of XYZ orientation on the inside of the Labyrinth: spatial movement and balance. Time, or rather the inverse of time in Hz and frequency cycles/s in the perception of pitch on the inside the Cochlea.

Van Dillen’s compositions in the series Elements can be listened to in several ways. Traditionally these are: privately over loudspeakers or headphones, or in a concert situation, that somewhat awkward setting where a group of interested people are sitting immobile and listening to what comes out precorded out of a professional loudspeaker system, with no apparent performers in sight.

Each of the Elements is created to be able to stand on its own, as a deeply composed and serious work of art, to be enjoyed on its own. Yet the Elements series as a whole has also been conceived to work and sound together as a larger ensemble: a potential meta-symphony of works, to be exhibited and enjoyed in an architectural sound installation of a variety of Elements set to play on repeat.

For installation playback of the series Elements, van Dillen proposes this option of creating simultaneously playing (looping) versions of various Elements widely spaced apart over a large space or several neighbouring spaces. Listeners could actively move around through the music or choose to linger or sit in certain spots for some time.

Also at home, a smaller version of an installation can be realized by playing several (looping) compositions in adjacent rooms, so they somewhat overlap and audibly interact. The only thing needed is one playback device per home installation element.

It is the composer’s wish that he himself as well as others will be able to create an ever-evolving range of different choreographies for various architectural installation performances of these works in the future, of diverse sizes and durations, ranging from the very intimate to the truly monumental and everything in between.

If such architectural installations are placed in a museum, they will allow for interaction with visual arts as well, but they could also be put in very dark settings.

Meanwhile at home, the listeners are challenged to DIY DJ and mix two or more of these compositions and turn one’s home into a personal theatre or museum.

A degree of inclusion of the listener into the process of creation can thus be achieved.

Elements of both Music and Chemistry

The Elements referred to in the title are obviously the chemical elements: the very first of the periodic table of which is Hydrogen with its remarkable isotopes Deuterium and Tritium, the only isotopes with their own chemical abbreviation. Less obvious from the titles is the use of Elements of Music, as described in his original approach to composing: his method (not a system) of prepositional analysis, developed from 1998-2011 by van Dillen.

Prepositional analysis is a new approach to the creation and analysis of music, not restricted to any style or vocabulary, but based on how humans hear music and perceive its elements Sound and Silence in interaction. Sound manifests itself in spectrum, time, and space, and from this observation 5 categories are derived, which sum up to 6 with silence included. These both include and transcend Stockhausen’s 5 dimensions of sound (pitch, duration, volume, timbre, and place). Based on the interactions a set of 22 prepositional analytical concepts is postulated, for use in creative composition or analysis.

These elements of music have in fact been used for a longer time and some if not all of them can be found in music history. In the work on this album, they are used to create new music inspired by the chemical elements. The chemical elements being such basic building blocks of matter, represent the basis for every existence, and for life.

By means of Mendeleev’s system for natural matter, and thus for material nature, van Dillen ventured to compose his meta-symphony Elements.

In his youth, Van Dillen spend quite a lot of (sometimes dangerous) time in his own small chemical laboratory, being patiently and lovingly inspired, coached, and sometimes warned by his uncle the professional chemist Hugo Wertheim.

This series Elements is an elaboration of this lifelong love for the basic building blocks of matter as it formed in the millions upon millions of years following the Big Bang.

Beryllium

Beryllium (Be) is the lightest of all the alkaline earth metals, and a strange one as it does not form ions. It is a rather rare element too, named after the precious stone beryl, a gem, from which it can be extracted with great difficulty.

Beryllium is unusually rare for such a light element. Almost all larger than Hydrogen elements are formed in stars, as a consequence of the nuclear fusion in their core, but in this too Beryllium is an exception. Along with Lithium and Boron, atoms of the element Beryllium cannot survive long inside stars and will form other elements before being ejected into space. It is assumed therefore that Beryllium is formed in interstellar dust clouds instead, by the influence of cosmic rays splitting up heavier elements.

Music of Beryllium

The music of Beryllium is a free pantonal polyphony of registers rather than of pitches or linear melodies. Registers used include the extremes, and extend far beyond the instrumentally feasible – a true electronic music therefore. One can clearly discern the references to outer space.

Whereas the music of Calcium (an important organic chemical component) is very much a musica humana instrumentalis by virtue of its registers and sounds, Beryllium (not part of vital organic chemistry) is represented by an opposite musical approach, much more abstract, and not resembling human instrumental music at all.

With the extensive presence of a variety of musical events in extreme registers, both high and low (the composer used 9 such distinct registers xtreme hi – very hi – hi – hi mid – mid – lo mid – lo – very lo – xtreme lo, the outer 4 of which are not found in instrumental music), in a way this music represents the emancipation of timbre to tone.

In its own way, the music of Beryllium became a gem too.

As in the other music by van Dillen for elements in group 2, a layered spectral composition process was chosen.

Instead of glissandi and lines, a three-layer counterpoint of relatively small pitched noise clouds form the basis together exploring the full register of audible frequencies. This basic cell was then reversed, inverted, stretched and transposed and brought in counterpoint with itself.

Thus thorough-composed to create the full form, in its spectral graph/score the partial counterpoint can be recognized. The two channels of stereo can be seen in the image below, and they are at times rather different because an ultra-wide almost surround sound space was used.

Photo credits:

Photo Oscar van Dillen by Elise van Rosmalen

Additional images from Wikimedia Commons

OIJ Records 028 – Donemus DCV 457